Cardinality Estimation Benchmark

Cardinality Estimation Benchmark

In this blogpost, we want to go over the motivations and applications of the Cardinality Estimation Benchmark (CEB) which was a part of the VLDB 2021 Flow-Loss paper.

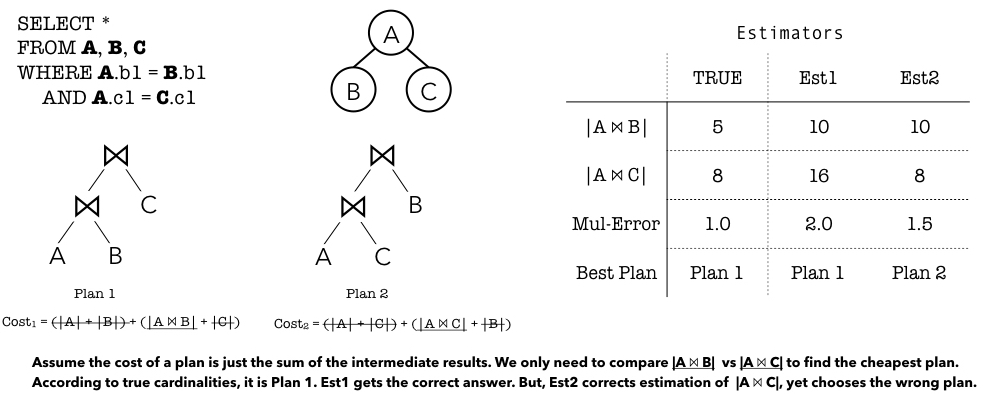

There has been a lot of interest in using ML for cardinality estimation. The motivating application is often query optimization: when searching for the best execution plan, a query optimizer needs to estimate intermediate result sizes. In the most simplified setting, a better query plan may need to process smaller sized intermediate results, thereby utilizing fewer resources, and executing faster. Several approaches have shown that one can consistently outperform DBMS estimators, often by orders of magnitude in terms of average estimation accuracy. However, improving estimation accuracy may not necessarily improve an optimizer’s final query plan, as highlighted in the following simple example1.

In order to build large workloads to evaluate the impact of cardinality estimators, we introduce a novel programmatic templating scheme. We use it to generate over 15K challenging queries on two databases (IMDb and StackExchange). More crucially, we provide a clean API to evaluate cardinality estimations on all of a query’s subplans with respect to their impact on query plans.

Example

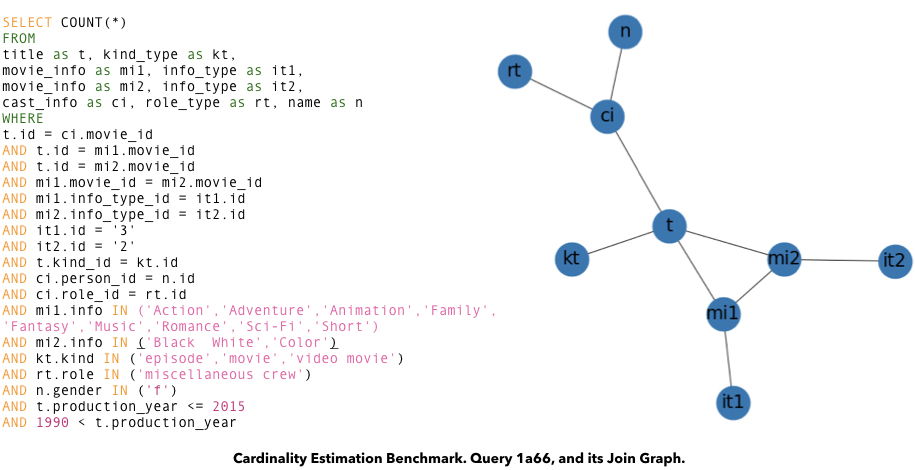

Consider query 1a66 from CEB-IMDb, shown below. A cardinality estimator provides the size estimate for each of its subplans (every connected subgraph of the join graph is a potential subplan we consider). CEB contains true cardinalities for all these subplans.

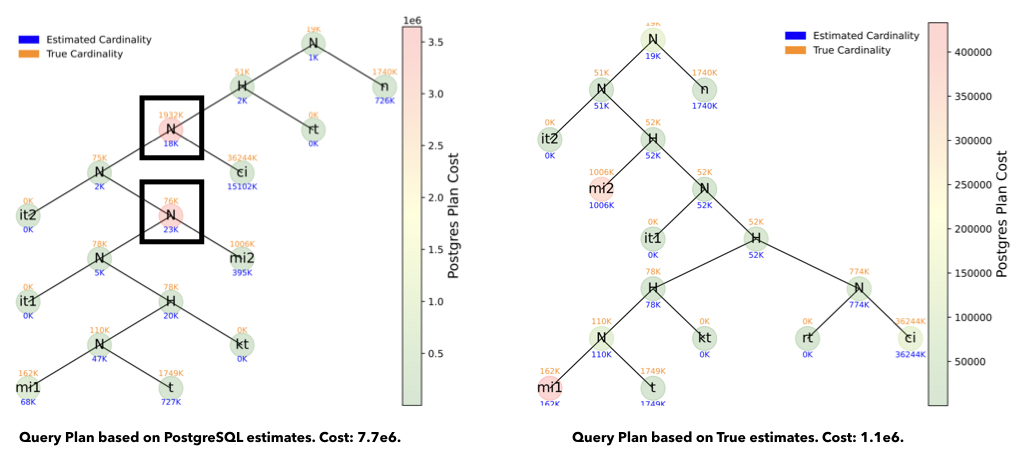

The subplan cardinality estimates can be fed into PostgreSQL, which gives us the best plan for these estimates. The cost of this plan using true cardinalities is the Postgres Plan Cost2. Below, we visualize these plans when using the PostgreSQL cardinality estimates (left), which is almost 7x worse than using the true cardinalities (right).

Each node is a scan or join operator. The colorbar for the nodes goes from green to red, i.e., cheap operations to expensive operations. Thus, looking for the red nodes immediately shows us why the estimates messed up: PostgreSQL underestimated cardinalities of two key nodes (highlighted in the left figure), and thus, using a nested-loop join was a bad choice — since the true cardinalities of these nodes were large, and would therefore require a lot more processing. This is a common pattern of PostgreSQL cardinality underestimates resulting in bad plans. That being said, we also see examples in CEB where PostgreSQL gets a worse plan due to overestimates, or other subtler motifs.

You can test your own cardinality estimator using our python framework in the CEB GitHub repository. You just need to provide the estimates for all the subplans, and it should evaluate those estimates based on Q-Error, or different Plan Costs (e.g., using the PostgreSQL backend, or a simpler cost model).

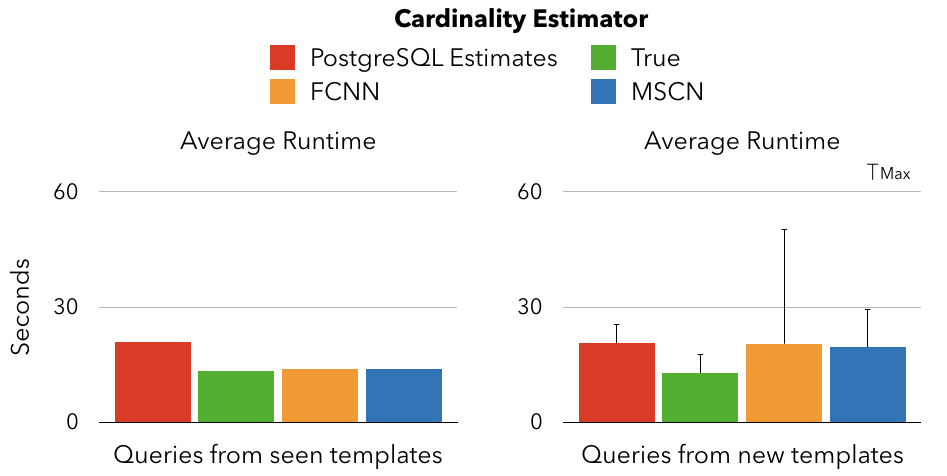

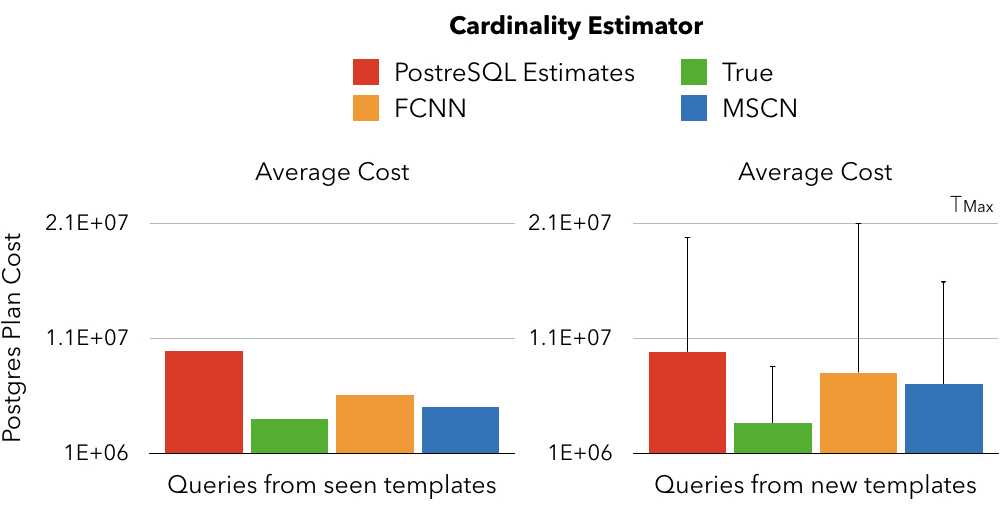

We provide a simple featurization scheme for queries, and data loaders for PyTorch, which we use to train several known supervised learning models in the CEB repo. One of the key results we find is that when the query workload matches the training workload, learned models tend to do very well in terms of query plan performance, but when the workload changes somewhat, the learned models can be surprisingly brittle:

The figure on the left has the training / test set queries split equally on each template (only test set results are shown). We see even the mean of almost 6K queries shows a large gap between PostgreSQL estimates and learned models — this translates to several hours faster total runtime of the workload. The figure on the right splits training / test queries such that queries from half the templates are in the training set, and the rest are in the test set. Since we have only a few templates, the performance can be very sensitive to the particular seed used to do the split, therefore, we show the results across ten such splits (seeds = 1-10). Observe that there are some extreme splits where the learned model performance can degrade dramatically.

These trends are also reflected when we use Postgres Plan Cost as the evaluation metric:

Computing runtimes is significantly expensive — and this experiment shows that we can often rely on trusting the Plan Cost evaluation metric instead, although the exact relationship between the runtimes and the plan costs should be an open research problem.

Why Is This Benchmark Needed?

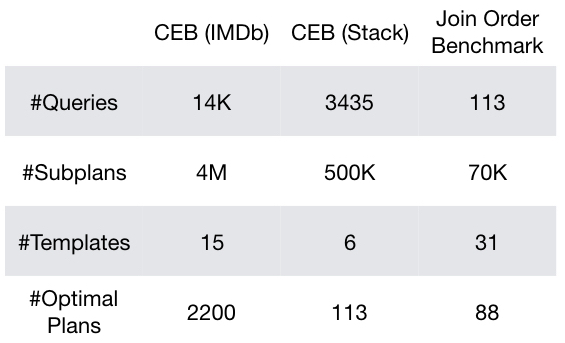

The Join Order Benchmark (JOB) did a great job of highlighting why TPC-style synthetic benchmarks may not be enough for evaluating query optimizers, in particular, the impact of cardinality estimation. In the CEB repo, we also provide cardinality data for JOB, and other derived workloads, such as JOB-M, or JOB-light, so they can be as easily evaluated with the tools described so far. However, even though JOB illustrates query optimization challenges, it contains too few queries for a cardinality estimation benchmark suited to the deep learning style models often used today. The table below shows key properties of CEB compared to JOB.3

There are several reasons why a larger benchmark is useful. Two critical motivations for us were:

-

Query-driven models require large training sets. Models, such as MSCN, Fully Connected Neural Nets (FCNN) / XGBoost, or Fauce learn from representative workloads. Therefore, having <= 4 queries per template, such as in JOB, is not great for training such models. Note that there are no shortage of representative SQL queries in industry settings — thus, the potential benefits of query driven approaches make it a compelling use case to study. Under appropriate circumstances, benefits over data driven models include: significantly smaller sizes (e.g., Neurocard models for a restricted subset of IMDb takes 100s of MBs, while MSCN style models are < 2MB), flexibility to support all kinds of queries (e.g., self-joins or regex filters), uncertainty estimates (Fauce), incorporating runtime information as features — such as estimates from heuristic estimators (proposed here), sampling (e.g., see sample bitmaps proposed in MSCN).

-

Gaining confidence in deep learning models through rich execution scenarios and edge cases. For traditional cardinality estimation models, which were based on analytical formulas, we could be confident of their functioning, including shortcomings, based on intuitive analysis. A lot of the newer models are based on deep learning based black box techniques. Even when a model does well on a particular task — it does not guarantee that it will have a predictably good performance in another scenario. At the same time, there is a promise of huge performance improvements. One way to gain confidence in these models is to show that they work well across significantly different, and challenging scenarios. Thus, the techniques used for developing CEB aim to create queries with a lot of edge cases, and challenges, which should be useful to study when these models work well, and when they don’t. This should let us study their performance in various contexts — changing workloads, changing data, different training set sizes, changing model parameters, and so on.

Next Steps

We would love to get your contributions to further developing CEB, or exploring research questions using it. Here are a few ideas:

-

Adding more DBs, and query workloads. There are a lot of learned models for cardinality estimation, and very few challenging evaluation scenarios. Thus, it is hard to compare these methods, and to reliably distinguish between the strengths and weaknesses of these approaches. There are two steps to expanding on the evaluation scenarios in CEB. First, we need new databases — for instance, if you have an interesting real-world database in PostgreSQL, then providing a pgdump for it should allow us to easily integrate it into CEB. We provide IMDb and StackExchange, and plan to add a couple of others in the future. Secondly, once we have a new database, we require query workloads for those. We have provided some tools for automated query generation, but at its core, all such methods would require some representative queries thought through by people familiar with the schema. This is the most challenging step for expanding such benchmarks, and we hope that open sourcing these tools can bring people together to collectively build larger workloads.

-

Limits of the learning models. The paper Are We Ready For Learned Cardinality Estimation? won a Best Paper award in VLDB 2021. They ask several important questions about learned cardinality estimation models, but their experiments are restricted to single table estimations, i.e., without joins. CEB should provide the tools to ask similar questions in the more complex, query optimization use case of these estimators.

- Data-driven models. Comparing unsupervised learning models (e.g., NeuroCard, DeepDB, BayesCard) with the supervised learning models. Some of these approaches are harder to adapt to our full set of queries — it involves modeling self joins, regex queries, and so on. Working to extend the data-driven approaches to these common use cases should be interesting. But we also have also converted other simpler query workloads, like JOB-M as used in NeuroCard, to our format, and provide scripts to run them and generate the plan costs etc.

-

Different execution environments. In the Flow-Loss paper, we mainly focused on one particular execution scenario: single-threaded execution on NVMe hard drives, which ensured minimum additional noise and variance. We have explored executing these queries in other scenarios, and we notice the runtime latencies fluctuate wildly. For instance, when executing on AWS EB2 storage, even the same query plan latencies can fluctuate due to the I/O bursts. On slower SATA hard disks, we find all the query plans get significantly slower, thus potentially causing many more challenging scenarios for the cardinality estimators. Similar effects are seen when we don’t use indexes. These effects can also be somewhat modeled by different configuration settings — which would allow Postgres Plan Cost to serve as a viable proxy for latencies in these situations. These queries, and evaluation framework, provide many interesting opportunities to analyze these impacts.

-

Alternative approaches to cardinality estimation. Another interesting line of research suggests that query optimizers should not need to rely on precise cardinality estimates when searching for the best plan. This includes plan bouquets, pessimistic query optimization, robust query optimization, and so on. For instance, pessimistic QO approaches have done quite well on JOB. It is interesting to see if they can do equally well on a larger workload, potentially with more edge cases, such as CEB.

- Featurization schemes. Our featurization makes simplifying assumptions, such as already knowing the exact templates that will be used in the queries and so on. This may be reasonable in some practical cases, like templated dashboard queries, but will not support ad-hoc queries. Similarly, models should be able to support self joins without knowing the templates beforehand, and so on.

We envision CEB to serve as a foundation for benchmarking (learned) cardinality estimators. We hope to add additional database backends besides PostgreSQL, and several other databases and query workloads, in order to build a much more challenging set of milestones for building robust and reliable ML models for cardinality estimation in a query optimizer. Please contribute!

Notes

-

Intuitively, this is because to get the best plan, you only need the cost of the best plan to be the cheapest. So for instance, large estimation errors on subplans that are not great, would not affect it. There are more such scenarios in the Flow-Loss paper. ↩

-

Postgres Plan Cost (PPC) is based on the abstract Plan Cost defined in the excellent ten year old paper, Preventing Bad Plans by Bounding the Impact of Cardinality Estimation Errors by Moerkotte et al. They also introduced Q-Error in the paper, which has been commonly used as the evaluation metric of choice in recent cardinality estimation papers. PPC is a useful proxy for query execution latencies in PostgreSQL, based on its cost model, but it is not DBMS specific. For instance, we have the basic ingredients for a hacky MySQL implementation here. PPC is useful because executing queries can be very resource intensive, noisy, and so on. Meanwhile, PPC can be computed almost as easily as Q-Error, and it is more closely aligned with the goals of query optimization. And these don’t always agree. For instance, we have seen scenarios where an estimator has lower average Q-Error, but higher Postgres Plan Cost. We show its correlation with runtimes, and further discuss the use of the Plan Costs in the Flow-Loss paper. ↩

-

A new benchmark was released last week, which has similar motivations as CEB. We have not yet had the time to look at, and compare it with our benchmark. ↩